|

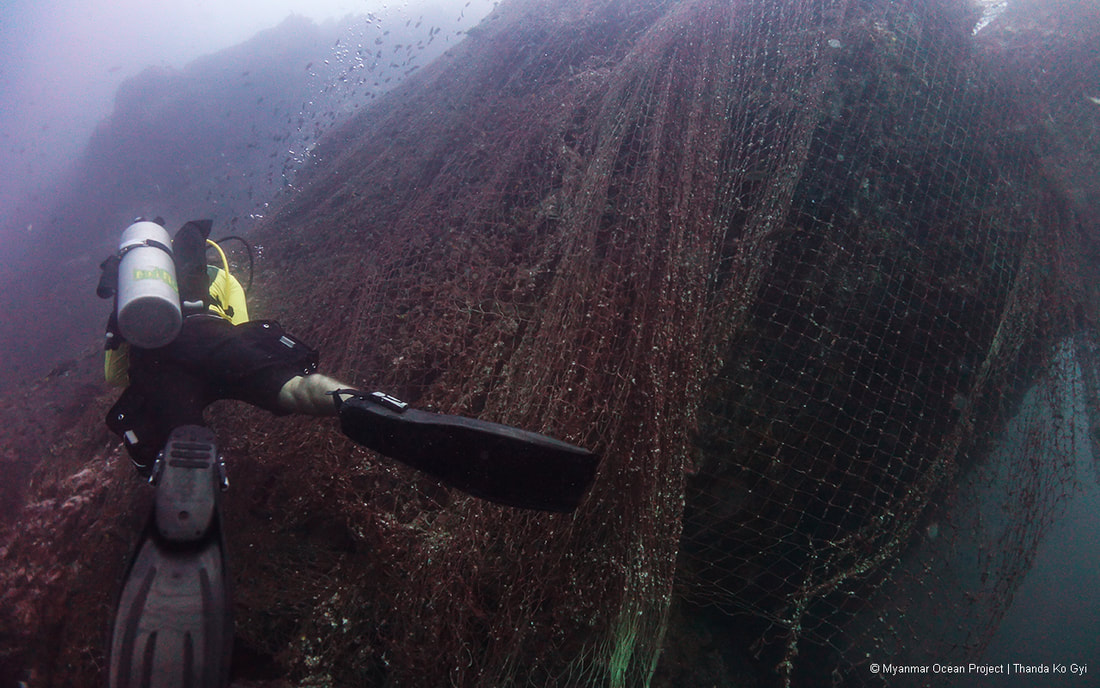

By Thanda Ko Gyi Over the past 12 months, I didn’t have much time to myself. Rushing from one Myanmar Ocean Project expedition to the next, there was little time to relax and even less time to absorb everything my team and I had experienced over the course of our field trips. When COVID-19 put our plans for the rest of the season to an abrupt halt, I found myself with a scarce resource: time. I decided to take these weeks of isolation to organise my thoughts and reflect on everything that has happened in this past year. The result? I realized how incredibly proud and grateful I am for the life-changing and fun experiences I’ve had through my work with Myanmar Ocean Project. Here are three things that put a smile on my face and maybe on yours too: 1. We removed nearly two tonnes of harmful fishing gear from the ocean When we set out on our first-ever survey expedition into the Myeik Archipelago in early 2019, we had no idea what to expect. Our goal was to collect data on derelict fishing nets in as many locations as possible and research its underlying causes and impacts. But would we actually find the places, where abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) accumulates? How many nets would our small team of divers be able to remove? 11 months, 89 dive sites, and hundreds of dives later, our team has extracted over 1,800 kg (yep, that’s right!) of discarded fishing gear from Myanmar’s beautiful underwater world. What does that mean? It means that in those places, coral reefs can thrive again without being suffocated by layers of fishing nets, crustaceans and juvenile fish can grow up without getting injured or killed in net entanglements, and fishermen should see fish populations rebound in the future. If you look at the big picture, of course, this is just a drop in the ocean. Myanmar’s ocean still holds thousands of tonnes of discarded or lost fishing gear beneath its surface. We haven’t stopped the problem at its source - yet. But we are working on it and we can already see our advocacy efforts bearing fruits. 2. I’m a Myanmar woman After having lived abroad, away from my family and culture for over ten years, I struggled to fit in culturally and socially when I returned to Myanmar. It wasn’t until I went on my first Myanmar Ocean Project expedition that I began to embrace my differences. As it turned out, the combination of my Myanmar heritage and my outsider’s perspective was an advantage. As a Myanmar woman, my interactions with the communities were not limited to formal arrangements, where social norms dictate who can communicate and who can’t. Instead, I was able to engage with everyone in a more informal manner building trusted relationships with people across different communities. One day, I’d be having my morning coffee and a retired fisherman fixing a nearby building would strike up a conversation about Myanmar Ocean Project’s work and share his thoughts on the issue of discarded fishing gear. Another day, I’d be helping out giggling Moken girls in their kitchen and end up planning a Try-Scuba-Dive for them to show them their home reef from a different perspective. In some of the communities, the locals were so welcoming it started to feel like a second home for us. I’d never have thought that my mission to explore the scope, causes, and threats of discarded fishing gear would bring me closer to my identity as a Myanmar woman but I’m glad it did. 3. Our team rocks When you’re out on expeditions for weeks in a row, spending twenty-four hours a day together, it takes a lot of flexibility and humour to work effectively as a team (and not kill each other!).

I was lucky enough that every single person contributing to Myanmar Ocean Project’s work, may it be the captain, the boat boys, the volunteers from the community and villages, or the divers and researchers were nothing short of incredible. Some of our divers would be so enthusiastic to remove fishing gear I had to force them to sit out on dives to make sure they pace themselves. Our boat boys assisted our divers diligently from the surface on kayaks and put in extra hours to sort and store collected ghost nets properly. The kids in the village would await us at the pier in the mornings asking whether they could join us and help out in spotting and retrieving fishing nets. I never dreamt of being surrounded by such a dedicated, hard-working, and passionate bunch of people both below and above the water’s surface. Whenever the tasks in front of us seem overwhelming, I just look around me to find renewed motivation and inspiration. Thank you to my team and everyone involved for being part of this incredible journey! I can’t wait until we can start into the next chapter for Myanmar Ocean Project and work together towards a healthy ocean in Myanmar.

7 Comments

By Sophie Gotthard Eight curious faces are looking at me, waiting for the briefing to start. We’re sitting in a small semicircle to prevent the roaring engine from drowning our voices. The boat just left the sheltered bay a few hours from Dawei and we’re headed towards the tiny Moscos Islands for our first Sustainable Snorkel Guide training with local tour guides. Myanmar boasts an extensive coastline stretching over almost 2,000 kilometers. In the past few years, the country has increasingly opened up to tourists. Now that tourism is on the rise, many Myanmar expats are returning home from neighboring countries to seize the moment and open tourism businesses. Given Myanmar’s unspoiled shores, abundance of islands, and stunning marine life, snorkel and dive tourism are an obvious choice for anyone looking into the country’s tourism potential. It’s time for a quick icebreaker session. Thanda introduces our team and the purpose behind this training. She asks the tour guides to talk a bit about their background. After exchanging a few shy looks among each other, one of the tour guides named Ko Thet decides to take the lead. He’s quite tall and wearing ear piercings – something you don’t see every day in Myanmar. "For the past seven years, I worked in Koh Tao, an island on Thailand’s east coast. During the day, I was a boat boy on a dive boat, at night, I was a barkeeper in a tourist hotspot“. His English is good and he greets everyone with “Hello Darling”, a phrase he picked up from his Australian coworkers in Thailand. Ko Thet is used to working on a boat and dealing with tourists from all around the globe. However, he’s never been the one holding the briefing or taking people out for a snorkel. “I really love the underwater world and I want to learn more about it. In Koh Tao, I saw that tourism could also have negative effects on the environment so I want to make sure I do a good job in my country and keep the coral healthy.” In many countries, tourism is one of the most important sources of income. Worldwide, the tourism industry accounts for almost 300 million jobs. There are many examples of tourism bringing development and opportunity for locals. Take the world-famous dive site Pulau Sipadan in Malaysia as an example. You can walk around this tiny island in less than 15 minutes, yet it attracts thousands of tourists looking for pristine marine life and big schools of pelagic fish each month. These tourists require transportation, accommodation, food and drinks, dive operators, and so on. Locals that used to fish to provide for their families now have a range of tourism-related jobs to get involved in. Unfortunately, there’s also a dark site to marine tourism. If managed unsustainably, tourism can destroy the very things it is based upon and turn colorful coral gardens into sandy deserts. In Pulau Sipadan things almost took a turn for the worse too. After the dive site was discovered, unregulated marine tourism pushed the boundaries of the precious marine ecosystem. Burdened by careless divers, snorkelers, and increased boat traffic, coral reefs deteriorated. In 2005, the Malaysian government put a stop to this development by establishing a Marine Protected Area (MPA) and strictly limiting the number of visitors per day. Since then, tour operators are encouraged to practice responsible marine tourism. Sipadan’s reefs have been slowly recovering. Sipadan is known for its big schools of jackfish and barracuda. In Myanmar, marine tourism is just starting out. Therefore, training local tour guides around the coastal areas is a great opportunity to encourage marine-friendly tourism. Some basic rules include anchoring without damaging corals, teaching proper snorkeling technique to avoid kicking sand or coral, preventing marine pollution, and briefing tourists not to touch or take anything. We finish the introduction round and are stunned by the diverse backgrounds of the guys around us. Some of them used to work in mining or construction, others in bars. One of them is studying law. Ko Htike, a wiry, quiet man, whose whole face brightens up when he smiles, is a fisherman. He’s used to spending long hours out at sea, but he decided to protect the marine environment from overfishing and instead show its beauty to tourists from all over the world. Everyone listens carefully to what we say. I’m surprised and happy that everyone is so eager to learn new things. After about an hour we reach the first island. A dense, green jungle is covering the terrain, gently sloping down and opening up into protected little coves with unspoiled beaches. It’s stunning. We start our briefing with some basic things guides should be aware of when taking out customers on a reef trip. What should you organize before and during the trip, how do you give a proper briefing and how can you protect the coral throughout the tour. When we finally get into the water we're greeted by massive coral bommies covering the ground. Sadly, we encounter only a few fish. Some of the guys actually haven’t used snorkel gear before, so we start by setting everyone up and making sure they know how to use the gear properly. Although it’s not common to learn swimming in Myanmar, most of the guys are already good swimmers. We start to practice duck diving with snorkel and fins. This will help the guides to point out marine life to their customers. We keep practicing and I’m happy to see how keen everyone is to improve their technique. We get back on the boat and drive to the next spot. Some snacks and a little debrief later, we have arrived at the next site. This time we’re concentrating on the different fish species. There’s more life around this spot, so we’re taking a waterproof slate to refer to the marine life we're encountering. A few beautiful Moorish Idols are passing by. A white-orange striped clownfish is hovering over his anemone protecting it from intruders. A moray eel is sticking its head out of a crevice. Now we can use our new skills and duck-dive down to have a closer look at the things we see. The reef seems relatively healthy, but I discover some areas with early coral bleaching and point it out to my fellow guides. After another hour we leave for our last destination of the day. It’s another stunning bay, but as soon as we get into the water, we discover a big fishing line. We follow it along the reef. It seems endless and is entangled in many different types of corals. We take turns diving down to safely remove the line without damaging the reef. Quite the task with such a long line! In the end, we emerge with a whole bunch of nylon ropes. Now the guides also know how to remove fishing nets or lines without breaking off any coral. Time flies and suddenly the captain says we have to head back to the mainland before it gets dark. The next day, we continue our training with a workshop on marine life and threats to the ocean. Ko Thet asks us whether we’ll be back for more training sessions. “I’d really love to try scuba diving as well. I’ve never had the chance in Thailand”.

We’re excited everyone wants to learn even more and feel encouraged to hold more trainings for tour guides along the coast. Yes, we’ll be back – maybe even with some scuba diving equipment. But for now, we’re headed to our first cleanup expedition further out in the Myeik Archipelago! By Mirja Neumann Ghost gear. What does this ominous term stand for? It refers to any type of fishing gear that’s been left behind by fishing boats - accidentally or on purpose. On our cleanup missions, we mainly find fishing nets, ropes, and lines, but we’ve also encountered some traps. Ghost fishing is what happens when these nets or lines are let loose in the ocean and continue to do their job without an owner. Invisible to fish, these ghosts catch whatever crosses their path. Given that their lifetime can reach up to 600 years depending on the material, this is a big problem. But why would a fishing boat drop its nets in the first place? Nets get stuck on rocks, coral, or other underwater structures, which prevents fishermen from pulling them back onboard. Nets rip and hence lose their value for the fishermen so instead of carrying the extra weight back to shore, they dump them in the ocean. Strong currents sweep away nets. Heavy catches make it impossible to haul them in. There are many reasons and therefore many nets in the ocean. Ghost nets are one of the biggest threats to marine life worldwide. Yet, unlike consumer plastics that end up in the ocean they’re not talked much about. Underwater, out of sight, out of mind. As divers, we’ve seen hundreds, no thousands of them. They’re everywhere. Some places look like fishing gear graveyards. It’s a topic that needs to be addressed. You need to be aware of it because it will affect you at some point as well. Here’s everything you need to know about this silent killer in the ocean. 1. It kills marine life. Big time.Once fishing nets are torn away, lost, or abandoned, they drift around in the currents until they get stuck somewhere or have collected enough organisms to sink to the bottom under their weight. Ghost nets suffocate, drown, maim, and starve hundreds of thousands of marine animals including turtles, sharks, mantas, and whales each year without being of any use to the fishing industry. In fact, an estimated 90% of species caught in ghost nets are of commercial value to fisheries. Since the cycle of killing can continue for decades, you can imagine the economic losses it causes. Corals, the base of the maritime food chain, are also affected by ghost nets. When nets settle on top of sensitive habitats such as coral or seagrass beds, they can damage the tissues of the organisms and smother whole underwater landscapes. Since the nets travel with currents for long distances, they can also spread parasites and invasive species, which cause great harm to marine ecosystems. To sum it up, ghost gear is one of the most lethal threats to a healthy ocean. If the pollution through ghost gear continues at its current rate, fish stocks will be depleted with severe consequences for local communities as well as the fishing industry. 2. It contributes to the world’s plastic crisis.A few decades back, fishermen mostly used gear made from biodegradable materials like cotton, hemp, or wood. In the early twentieth century, the invention of synthetic fibers changed the fishing industry dramatically. Handcrafted cotton nets were replaced with non-biodegradable, durable, lightweight nets made from plastics. Today, the majority of fishing nets consist of nylon. While the strong, light nets ease the immediate burden on fishermen, they pose a great threat to marine life, the fishing industry itself, and seafood consumers. Why? Synthetic fishing nets take decades, some parts even hundreds of years to decay. Every single net that found its way into the ocean may be floating around the ocean without an owner, silently killing and maiming marine life for its entire lifetime. Once the nets start breaking down, the small particles or microplastics are ingested by fish, shellfish, coral polyps, and other marine creatures. If the amount of ingested microplastics doesn’t kill the organisms from the inside, it gets passed up in the food chain and ends up on our plate. We’ve all heard about the massive garbage patches, where ocean trash gets rounded up by the currents. A recent study suggests that roughly 46% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch consists of lost or abandoned fishing nets. With a whopping 640,000 tons of nets added to the mix each year, ghost nets are the single biggest contributor to the ocean’s plastic crisis. 3. It spoils tourism.Despite its fatal consequences for the fishing and seafood industry, ghost nets also affect people trying to make a living off tourism. Beachgoers, snorkelers, and divers want to see pristine shorelines and bustling coral reefs, not dead coral gardens and oceanic litter. Additionally, nets can damage boats by entangling propellers and anchors. Cleaning up ghost nets is a costly and time-consuming investment that not everybody can afford. However, if nets are not cleaned, tourists don’t return and the financial loss for the tourism industry gets even bigger. 4. There’s no magical cure to it.How amazing would it be if some genius just invented a cure to make this problem go away? Unfortunately, the odds for that happening are extremely low.

Recovering ghost nets from the ocean as we do in our expeditions around the Mergui Archipelago is only a short-term solution to save local marine environments. There’s more organizations like ours helping to remove ghost gear from the ocean in other parts of the world. However, we need to tackle the root of the problem to make a difference. Ghost fishing mostly takes place in the middle of the ocean. Some fishermen, island communities, and tourists may come across it, but the majority of people will never see the problem with their own eyes. Bringing this issue to the public’s attention through reporting on the scope of the problem is the first step to finding a sustainable solution. Strict regulations for the disposal of fishing nets would be the next, obvious attempt to tackle the ghost gear issue. The problem is that commercial fishing predominantly takes place in the open ocean, in international waters, which makes any sort of regulation and enforcement extremely difficult. A few local governments have worked on this issue, but it requires all stakeholders to come together, agree upon appropriate measures, commit to enforcement and set aside a budget to actually make progress. Achieving this will take a long time. Too long. So what can you do on a personal level? Despite supporting organizations and individuals that spend their day working on this issue, you can help us spread the word about ghost gear. If you’re a seafood lover, you can make an effort to eat seafood that’s been caught sustainably. That means inquiring about the area, where the fish has been caught and finding out about the fishing technique as some fishing gear is more destructive for the marine environment than others. By Sophie Gotthardt Our boat is gently rocking side to side with the rhythm of the waves crashing against it. The sky is clear and the late afternoon sun gives everything a golden glow. I can already see that the sunset will be beautiful, but right now we’re racing against the clock. We’re in search of something big. “We’re not far off!”, yells the captain. His voice is almost completely drowned in the clattering sound of the engine. We’re standing on our boat’s roof, trying to counterbalance the vessels swaying movements while covering our eyes from the blinding sun with both hands. Everyone is watching the movement of the water closely, looking for any clues about what might be awaiting us below the surface. Sunset is getting closer and we’re running out of time. Diving with strong currents is one thing, but doing so while it's getting dark can be dangerous. We’re on a treasure hunt. Our mission is to find a big, submerged pinnacle, in fact three of them in close proximity - a place only a handful of local fishermen are familiar with. But why do we need to find this particular spot? The goal behind our expedition to the Mergui Archipelago is to survey and identify ghost net hotspots. That means we’re looking for sites, where discarded fishing nets get entangled and endanger marine life. So what does that have to do with our mysterious pinnacle? Once a net gets dropped into the ocean it floats with the current until it gets stuck somewhere, possibly on a rock, a coral bommie, or a pinnacle. The pinnacles we’re searching for are located right in between the open ocean and an island channel, where currents get really strong because big water columns are squeezed through a small area. The currents carry anything from driftwood, plastic trash, and fishing nets into the open ocean. Our pinnacle rising up from the ocean floor is one of the few obstacles for drifting matter to get entangled. Why are nets stuck on a random pinnacle a problem? Strong currents don’t only bring lots of trash and nets. They also bring a staggering amount of marine life. Currents carry plankton and larvae from many places, leading to high biodiversity and wide gene pools wherever they pass by. Pinnacles in particular offer a rich substrate that corals, sponges, and other marine life use to form nurseries, which are, in return, a safe shelter for larvae and juvenile reef fish. Healthy and diverse reefs help to sustain the food chain for bigger predators like trevallies, groupers, and sharks. In addition, pinnacles in the open ocean offer a rest stop for big pelagic fish like manta rays and whale sharks. Pelagic species like oceanic manta rays or sharks use these oceanic oasis for getting cleaned by cleaner wrasses in what we call a cleaning station. In other words, pinnacles in the open ocean are often teeming with marine life. Therefore, ghost nets can cause a great deal of harm in these spots. Imagine a big nylon net getting stuck between two underwater pinnacles. The net will undoubtedly injure and kill lots of marine life without being of any use for the fisheries themselves. Over time, it will reduce not only the biodiversity of the ecosystem but also the catch of fishermen in the area. How are we helping? Removing nets from biodiversity hotspots, like our pinnacle, is, of course, only a short-term solution. The long-term goal must be to protect the area and prevent ghost nets from ending up in these places. It is by collecting data and proving the existence of a biodiversity hotspot for threatened or endangered species like the oceanic manta ray that we can make a difference. Establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPA) can help to put a stop to unsustainable fishing practices and make the health of Myanmar’s ocean a priority. “I think there might be something over here!“, Ben shouts through the engine noise pointing northeast. The surface looks perfectly flat, a sign for upcoming water. Not too far from the same spot, the water appears choppy - a sign for a downward current? A quick look on my dive computer tells me that we have to jump in right now or we’ll miss our chance. We put on our gear, set our compass towards the direction of the suspected pinnacle, and jump in. Gripping onto the anchor line we slowly descend into the unknown. The visibility is poor and the ocean floor is still too far off to see. The current is dragging us south. 18 meters and still no sign of life. The water underneath us remains pitch-black like a starless sky at night. 20 meters and still nothing but darkness. Maybe we’re in the wrong spot after all? I’m looking back to check on my dive buddies. I can tell that Thanda is in between curious and concerned. Finally, we’re hitting the ocean ground. 31 meters. Everyone seems relieved that we reached the floor. We follow our compass heading and we find ourselves in an underwater desert decorated with a few whip corals, but not much life despite that. We slowly push our way forward into the unknown. Suddenly a school of yellow-tail fusiliers appears - a good sign that we are getting closer to a reef. Now I also start hearing the crackling sound of a busy reef. Still following the disappearing fusilier school I catch the sight of another passing school - a bigger one. The crackling sounds get louder. I turn around to look at my buddies. They seem just as excited as me. We’re onto something. Thanda gets her camera in position. A huge barracuda school appears and starts circling us. They slowly start forming a tornado and we’re in the middle of it! I almost burst out laughing. The barracuda school vanishes as quick as they appeared and opens the view to something much bigger - the pinnacle. We finally made it! After exploring this hidden paradise for a bit, the sunlight disappears. The sun has set. We have to ascend.

Everyone is excited about our discovery. In just one dive we had the pleasure to observe lionfish, surgeonfish, filefish, boxfish, parrotfish, pufferfish, butterflyfish, moorish idols, scorpionfish, pilotfish, big trevallies, fusiliers, barracudas, big groupers, and many more. We even spotted a potential cleaning station with five cleaner wrasses waiting for their next patient. We’re certain our pinnacle gets way bigger visitors passing by than groupers. And just as we’re about to leave this magical site, two mobula rays show up on the surface dancing with each other as if they wanted to reassure us. We're sad to leave already, but one thing is for sure: We’ll be back! By Sophie Gotthardt Two girls are sitting in the cushioned car seats between compressor, tanks, and other dive equipment aboard our self-proclaimed dive boat. A former fishing boat, the wooden vessel offers just enough space for our team to travel around the Mergui Archipelago, where we conduct our survey and cleanup missions. The boat has quite a big roof, perfect for storing our daily catch: discarded fishing nets. Today is not about retrieving ghost nets from the ocean though. We’re taking two girls from the village on their very first scuba dive. After holding a presentation about our project, Thanda asked the group if anyone would be interested in experiencing their home reef from a whole different perspective - as a diver. At first, no one dared to volunteer. A few girls exchanged shy looks and giggled. “We’ll give it some time”, Thanda said. “I’m pretty sure at least one of the girls will try it.” The next day, Thanda entered the kitchen while the 17-year old Htar Htar Linn, a half Moken half Myanmar girl, was cooking. “Would you like to try scuba diving?”, Thanda asked straightforward. She replied with a hesitant smile: “Yes, I'd like to. Can I bring my friend?” Fast forward to the next morning and the two girls are sitting here with us, trying on the dive equipment for the first time. Every time I catch a glimpse of one of the girls they smile and start giggling. They don’t speak English, so Thanda is translating everything I say. The boat engine stops. We’ve arrived at the other side of the island and are parked in safe distance from the shallow coral gardens in front of the Moken village. Htar Htar Linn and her friend Kin Lah, another Moken girl, laugh and say something in the Moken language that even Thanda can’t understand. The Moken, often referred to as sea gypsies, are a group of about 3000 semi-nomadic people who live and work around the 800 islands of the Mergui Archipelago. They spend the majority of their lives out at sea. Over the generations, they have collected a tremendous knowledge about the ocean that helps them to live in harmony with nature. Dependent upon the sea for their survival, overfishing, pollution, and climate change heavily affect their lifestyle. Today, many of them live in villages and instead of selling fish to consumers directly, they end up selling to bigger fishing fleets that export much of the catch to Thailand.  Htar Htar Linn jumping in with the dive gear for the very first time. Htar Htar Linn jumping in with the dive gear for the very first time. After a detailed briefing about the gear and underwater safety, we get everyone’s equipment ready and jump into the crystal clear water. Both girls are confident in the water. It’s easy to see they grew up surrounded by the ocean. Two little boys, no older than six, paddle by in their tiny nutshell. They point at us and laugh. This is probably the first time they’ve seen divers. We must look quite silly to them in all our gear. Moken people have fascinated researchers from all around the globe. Like the Sama-Bajau nomads from the southern Philippines, who can hold their breath for up to thirteen minutes, Moken are believed to have genetically adapted to life at sea. A study revealed that they can see twice as clear underwater due to a reflex that closes their pupils when diving down instead of opening it. Until now, Htar Htar Linn and Kin Lah have only been freediving. They can hold their breath for a very long time. For scuba diving, however, it is very important not to hold your breath and continue breathing in and out at all times. I’m watching the two teenagers take their very first breaths underwater. They look a bit spooked and excited at the same time. A few breaths later, the girls feel more confident and we are ready to go deeper. Thanda and I split the girls in between us so we can both look after them one-on-one. I’m with Htar Htar Linn, who swims remarkably fast and quickly wants to take the lead. I’m holding onto her tank to make sure she doesn’t slip away while we explore the reef. We’re only at about 3.5 meters of depth and surrounded by stunning, healthy coral. I point out three different types of branching Acropora coral just next to a massive Poritidae bommie. Considering the size of these coral bommies, they must be at least a hundred years old. I also spot my favorite coral, the Euphyllidae - or bubble coral - named after their grape-sized blobs. In the deeper end of the reef, we see many different sized Fungiidae, the mushroom coral, covering the sandy bottom. I’ve dived many different sites around the world, but I’ve never seen this species grow this big! About forty minutes later we make our way back to the boat. The girls are still pumped with adrenaline discussing their new experience with each other and laughing. Shortly thereafter they get picked up by a boat that takes them back to the village. They joke around with the boat boy. Without a doubt, they have something over all the boys in the village now!

While we’re headed to the next site for a survey dive, I’m day-dreaming about the first two Myanmar-Moken girls becoming certified divers and exploring the beautiful coral gardens of the Mergui Archipelago. Maybe on our next visit! |

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed